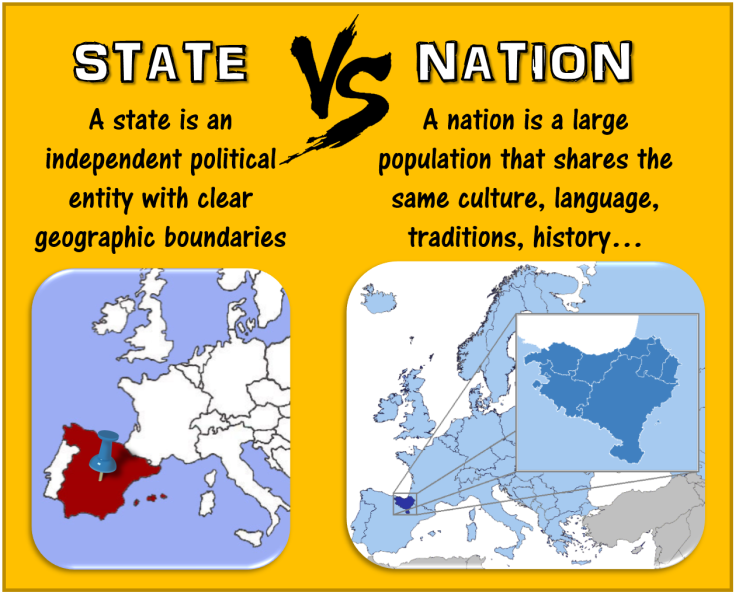

Perspectives on preserving the use of languages that are not official in a given state are limited. Nowadays, each state is a culturally and linguistically homogenizing polity, especially the nation-states in central Europe and in east and southeast Asia that are ethnolinguistic in their character. Communities that speak (and sometimes write) minority, regional and other non-official languages have two basic options of preserving their languages. First, they can make sure to stay isolated from the homogenizing state’s structures and institutions, especially from schools. Compulsory universal elementary education teaches (in other words, imposes) the official language to successive generations of children, ensuring that minority groups’ children are compelled to un-learn their community languages. Another possibility open to minority groups for preserving their languages is a struggle for their own autonomous or fully independent ethnolinguistic nation-states. None of these two options is appealing. The latter entails violence and even bloodshed, while the former means conscious disengagement from advantages (alongside disadvantages) of modernity. Hence, unless the strictures of the current legitimating model of modern statehood (that is, the homogenizing in its nature nation-state) are dramatically altered, then each of the still surviving non-state languages will become endangered in the span of three to five generations.

Continue reading “Minority Language Protection Legislation: A Sobering Note”

![Samuel Linde. 1807. Słownik Języka Polskiego [Dictionary of the Polish Language] (Vol 1)](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6a/PL_Linde-Slownik_Jezyka_Polskiego_T.1_Cz.1_A-F_001.jpg/250px-PL_Linde-Slownik_Jezyka_Polskiego_T.1_Cz.1_A-F_001.jpg)